What’s the point?

As a kid I had a nightmare. Two men came and stood next to my bed. Not really men. Humanoid. Shapes with color. One pink. One black. They just stood there and looked at me as I lay in bed.

My mom would often mention this dream. Apparently, it really freaked me out. Sleeping was hard for days. I don’t actually remember the dream. Often when I remember dreams what I remember are images. When reconstructing the dream I have to fill in narrative. The images I have of the pink and black humanoids are images I developed based on my mom’s retelling of the dream. Based on how hard I struggle to articulate dreams I have now, there are serious doubts about my ability as a 5 year old to accurately communicate a dream. I believe I said what my mom said I said, but I don’t believe what I said was true. As a result, the images of pink and black humanoid forms standing next to my bed are suspect.

Dreams have never much interested me. Maybe it’s because most my dreams are banal. I eat a bowl of cereal. I put on socks. Someone walks into a room and stands still. When they aren’t banal they feel too on the nose. A couple nights before I started teaching a writing course I had a dream that I was teaching a class in a cemetery and there weren’t enough seats. A straightforward expression of anxiety about teaching. Like eating cereal, banal.

I’m not interested in my own dreams and I’m definitely not interested in other people’s dreams. Some dreams are weird and funny. Entertaining to hear, but as soon as someone tries to extrapolate meaning from a dream I shut down. It’s pointless.

Dreams follow a dream logic. The waking brain doesn’t follow dream logic. To interpret them is to impose waking logic onto a dream logic. It’s like looking at a book in a language you don’t know, picking out some words that look similar to English words (regardless of whether or not they’re actually related to the English word) and assuming you understand the book. Foolish.

My interpretation of teaching in a cemetery is probably wrong.

I mention all this because the books I read this month deal with dreams and visions and finding meaning in both.

Enjoy!

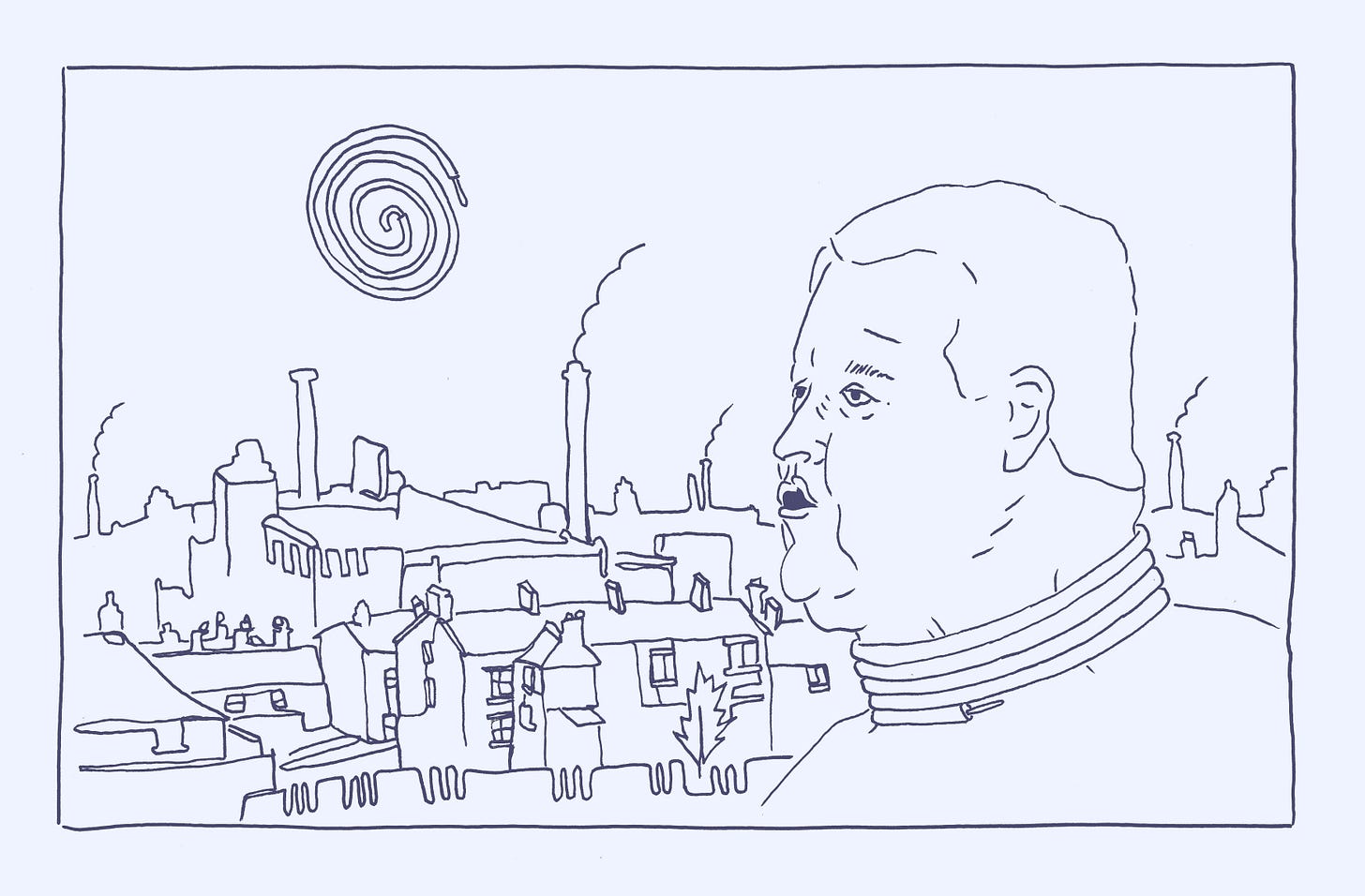

Solenoid by Mircea Cartarescu. First published in 2015. Translated from Romanian into English by Sean Cotter. Published by Deep Vellum in 2022

The nameless narrator of Solenoid has lice. He teaches Romanian at a high school in Bucharest. One student has lice and kindly shares it with everyone. Not unusual, sadly. Tiny twine sticks out of his belly button. When he was born the twine was used to tie off his umbilical cord. Bit by bit he pulls it out and saves it along with a tin full of his baby teeth. Solenoid opens with a catalog of tiny body horrors.

The nameless narrator had a twin brother. As a child he was ill and disappeared. Probably died, but the narrator doesn’t really know. As a child his mother said she was taking him to a friend’s house to play. Instead they went to the dentist. Maybe the dentist was demented and did painful experimentation on him, or maybe it was a normal dentist visit. Normal dentist visits are demented and painful.

The nameless narrator got sent to a boarding school for kids with tuberculosis. Unsurprisingly the school is like prison. Most boys wet the bed because they’re beaten for leaving their rooms at night. They are heavily medicated. One boy, Traian, tells all the other boys what death will be like.

Death is not the end of life. After we die, there’s a long journey ahead of us. It feels like we are traveling down a long road, very twisty and very dark, all at night. There are no stars in the sky, in fact we don’t know if there even is a sky. There is just a road that stretches ahead, where we walk in silence. From time to time, our road crosses another, where another person who has just died is also walking. And then another. Because each road only has one soul. We only meet and look at each other at the crossroads, and how we look scares us. Because we don’t look like people anymore. We are different. Some of the dead, after pausing at the intersection to look at each other, continue down their path. Others decide to trade fates, and then, after they embrace mournfully, each walks down the other’s road. Because after you die, you know what’s waiting for you. You wander for thousands of years on roads that cross forever, sometimes you must stay in this giant node surrounded by the night, to eternally meet dead people, all with the same inhuman face, all silent and worried. I have seen this kind of people in my dreams, they have pale faces, big eyes like flies, narrow lips. They have thin necks and discandied arms. They glide down their roads, looking at them is scary…

Traian encourages the narrator to secretly not take his medicine. Together they flush pills down the toilet. Instead of falling into a medicated sleep they see school staff enter the room at night, take sleeping kids out of beds, drag the sleeping kids to a room in a basement with a dentist chair. The school staff does demented and painful experiments on the children.

As a college student the nameless narrator writes an epic poem. The poem is so good. So true. The poem reveals that reality is false and the poem is the only true reality. The poem, called “The Fall” is going to make him a literary star. He reads the poem at a writing workshop. It’s mocked and criticized. He never writes again. Writing workshops are demented and painful.

Sometimes he imagines his life split in two. There is the life he lived. A middle aged teacher with a dull repetitive life. There is also the life he didn’t live, where his poem is well received by the reading group. He published the poem and became a famous literary star. Since the narrator struggles differentiating reality and unreality both lives are real to him. A double life. His twin reborn.

Large sections of the book recount the nameless narrator’s dreams. Like me, as a kid he had a dream that someone came into his room and watched him. That person, or that person’s colleagues, continue to visit him throughout his life. It’s unclear if these people are real, waking visions, or dreams. For most of his life he copies down his dreams. He believes there is a truth hidden in his dreams. A truth about his “anomalies.” Anomalies are what he calls his dream visits. Once he understands his anomalies all weird shit will stop happening to him. He is searching for truth and understanding and an end to anomalies.

The nameless narrator and a math teacher go to a warehouse near the school. Teens hang out in the warehouse. As they wander through the warehouse reality turns unreal:

I found myself in a kind of natural science museum, with showcases, dioramas, and aquaria lining the corridor. After no more than ten meters, the corridor ramified into a labyrinth of rooms and smaller rooms teeming with items on display, artificially colored biological specimens and hideous creatures in jars, with explanatory wall texts celebrating the exobiology of these nightmarish creatures… Monsters, monsters that the mind can neither conceive nor house nor accept, suspended like spiders on glittering threads, monsters out of our ancestral reflexes, with pale skin, clattering teeth, eyes dropping from their sockets.

Several times throughout the novel the nameless narrator wanders into an unknown space and sees increasingly horrific creatures. Like Dante and Bosch. Often the journeys begin with or are connected to the narrator engaging with “picketists”-- what we might call “protestors.” Protesting death. Their signs read, “Down with death!”, “Down with illness!”, “Protest Pain!”, etc. “Do not go gentle into that good night” is their mantra. I don’t disagree. Death is demented and painful.

The nameless narrator lives in a large house shaped like a boat. The layout of the house changes. There are doors he’s never gone in. He explores the house but he never sees it all. Buried beneath his house is a giant solenoid. Five solenoids are buried beneath Bucharest. In his bedroom there is a switch. When he flips the switch the solenoid turns on and he is able to levitate. The physics teacher from his high school, Irina, who doesn’t believe in reality, visits regularly so they can have sex floating above his bed.

One day Irina and the narrator go through a door in his house he’s never gone down before. They follow a hallway. At the end of the hallway is a door with a porthole. Through the porthole giant monsters running to and fro. The monsters are larger than life mites.

As a kid the narrator was obsessed by a book called The Gadfly. Reading it for the first time made him cry. The Gadfly was written by Ethel Voynich. Ethel Voynich was one of George Boole’s five daughters. Boole was a significant mathematician. As a librarian I know him for “Boolean Operators” used to combine search terms.

Another of Boole’s daughters married another significant mathematician. The history of the Boole’s and their mathematical theories culminates in the nameless narrator reconnecting with the librarian from his childhood. The librarian intentionally placed books on the shelf, so the narrator would check them out and read them. The library was cultivating the narrator’s interests, knowledge, perception, and understanding of the world. All so to lead the narrator back to the librarian in adulthood. The librarian tells the narrator about The Voynich Manuscript. The librarian has a copy. He loans it to the narrator. The illustration on the manuscript exactly matches the countless dreams and visions the narrator has had throughout his whole life. From an early obsession with Ethel Voynich to relentless visits from dream people, to encounters with giant mites, to the discovery of a manuscript owned and named after Ethel’s husband, the narrator feels his life has come full circle. Everything was leading him here. His quest for truth and meaning has reached crescendo. With the librarian, who also lives above a solenoid, the narrator is validated in his search.

The librarian has a demented experiment to share with the narrator. He wants to send the narrator’s consciousness into the body of a mite. The librarian has developed a mite colony on his arm.

I created a world inside my very body, a network of channels through my dermis, constantly inhabited, explored, and expanded by a people that believes, as we do, that it is alone in the universe. Hundreds of generations have already passed since their Genesis, there must have already appeared in their world, a chemical glory: myths of their origins, of their totemic ancestors, of the perplexing creatures who gave them face and name only to then retreat into the imperceptible and incomprehensible.

It just looks like a rash. It is a rash. Specifically scabies.

If the narrator can enter the body of a mite and communicate something of his own world to the mites it would prove that salvation was possible. Communication with the transcendent, the existence of the divine would be possible. The narrator isn’t looking for salvation. He just wants to know salvation is possible. Certainty of the possibility of salvation would satisfy his quest for truth. For understanding. For meaning.

The narrator successfully becomes a mite. He speaks several different mite languages.

I used the Sqwiwhtl language, whose phonemes are the subtly rhymed waves of my own stomach, transmitted by placing it against other stomachs, and so on and so on, to the edges of the mass that surrounds you. And I used the language of Haaslaaslaah, which speaks in magnetic fields like enchanted harps, and which does not express concepts but rather pains, from the pain of a leg being pulled off to the abandonment of a belief. And I used the lofty language of flatulence and belching, suited to manipulating the crowds of the agora, like flowery language panders and sophists. It was difficult to tell them about the world outside, because the mites had no intuition of “outside.”

There aren’t words in the mite language to express concepts from the human world. The message gets muddled, confused, reduced. The language is wrong. It doesn’t fit. Too small. He returns to his human body and to the librarian. Salvation isn’t possible.

No salvation. No truth. No end to his dreams, his visitations, his anomalies. It all means nothing. The history of the Boole’s, the Voynich manuscript, the hellish landscapes he wanders through, the solenoid, none of it disguises a deeper meaning. None of it leads anywhere. His missing brother, the medical experiments, the monsters in the warehouse, the giant mites in his home, his baby teeth, his twine, his lice, the librarian's mites. Nothing. Despite the picketists protestations, he can’t escape death. No escape. No transcendence.

Irina is pregnant. They have a child together. It’s secret from their colleagues. Salvation isn’t possible, so the narrator stops his looking. Instead he focuses on what’s in front of him. It’s not transcendent. In the grand scale of the cosmos it’s meaningless, but Irina and his daughter are a type of salvation. The novel becomes increasingly apocalyptic. The narrator and Irina and the child run away. They hide in a church. Death is persisting and encroaching. Irina and his daughter make the encroachment bearable. Enjoyable even.

“We will stay there forever, sheltered from the frightening stars.”

Black Elk Speaks by John G. Neihardt. First published in 1932.

Unlike the narrator of Solenoid Black Elk knows reality. His visions are reality. They cannot be ignored. Ignoring them, ignoring reality causes illness.

Black Elk first had a vision when he was nine years old. One night while asleep in his teepee a voice calls him, tells him to behold. Black Elk crawls out of his teepee and sees a bay horse. He mounts the horse. First, Black Elk sees twelve black horses. The bay horse rotates and he sees twelve white horses. The bay horse rotates and he sees twelve sorrel horses. The bay horse turns and he sees twelve buckskin horses. Twelve horses for each of the four spirits. One spirit for each direction: North, South, East West.

All the horses get into formation and lead Black Elk to a rainbow teepee where the six grandfathers are conferencing. Each grandfather speaks to Black Elk. They tell him to take courage. With a spear and a hoop he goes on a journey. He sees generations. He has to climb several mountains. He becomes a spotted eagle flying over the world. He sees a man painted red who falls to the ground. When the red man stands up he is a fat bison. His people are running around frightened. He transforms back into himself. He’s on his horse again. He’s with the sixth grandfathers again. They tell him he has triumphed.

Twelve days passed while Black Elk experienced his vision. To the outside world he was sick and unconscious. His parents were worried. He didn’t tell anyone what he saw. He tried to ignore his vision. Reality.

Black Elk is part of a lengthy tradition of mystical experiences coming from extreme physical states, often illness. Slowly he recovers and continues to live life as an adolescent boy. A lot of history happens around Black Elk, but he’s too young to remember. His friends help. Standing Bear recounts a bison hunt. Both Standing Bear and Iron Hawk remember the battle where they “rubbed out Long Hair.” Long Hair is George Custer.

Crazy Horse was Black Elk’s cousin. They were close and Crazy Horse’s death has a massive impact on the young Black Elk. Again and again he says that the “wasichus” (white men) had to deceive and trick Crazy Horse. Otherwise they would never be able to defeat him.

Years go by. Black Elk is 17 and overwhelmed with fear. His parents take him to various medicine men. His mother is convinced his childhood illness has returned. Eventually he tells a medicine man his vision. The medicine man immediately understands. Instead of ignoring his vision Black Elk needs to share it. Sharing it is what makes it reality. The tribe needs to act out his vision. Once enacted, fear will disappear.

The tribe works together to put on a production of Black Elk’s vision. They collect all the necessary horses. Six old men play the six grandfathers. It’s a success. Black Elk is cured. During the performance others with ailments are cured too. After the performance he has the ability to heal. Now, whenever Black Elk has a vision he shares it with his tribe through performance. Doing so allows him to use the power embedded in the vision.

Black Elk joins Buffalo Bill’s traveling show. He travels to New York and hates it. He travels to England and meets the queen. The queen loves him. He thinks that if the queen were in charge of America maybe his people wouldn’t be treated so poorly. Black Elk and I disagree on this point.

The book ends with a description of the massacre at Wounded Knee. Black Elk survives.

I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream.

Black Elk’s story ends with Wounded Knee. No mention of what happened in Black Elk’s life between 1890 and 1930 when Black Elk spoke his life story to his son, Ben Black Elk. Ben translated his father’s words from Lakota into English, so poet John. G. Neihardt could hear, understand, and transcribe the experiences of Black Elk. In 1932 Neihardt published Black Elk Speaks1. In 1985 Raymond DeMallie published The Sixth Grandfather, which is the entire transcript of Black Elk’s conversation with Neihardt. From the transcript it is clear that Neihardt embellished and added to Black Elk’s story. My edition has footnotes denoting everything Neihardt added, which include some of the most quoted passages. I guess that matters to some people. Like, if you want pure Lakota culture and beliefs, or pure historical documents, or pure truths or whatever. The book has been marketed at various times almost as a religious text. If one were to take it as a religious text, or a work of ethnography I can see how Neihardt’s insertions cause troubles.

To me the book seems like a collaboration between an Oglala medicine man and an American poet. The interruptions from Standing Bear and Iron Hawk not only indicate the book has more than one author, but the truth cannot be reached through one perspective. Everyone is circling it, but truth is unknowable. Or the truth doesn’t belong to one person, one retelling. The truth is a collaboration. Taken together the various narrators, the severe loss experienced by the Lakota, the fraught relationship to truth, and the time period it was written and published make a case for Black Elk Speaks as a work of Modernism.

In the 1430s Margery Kempe orated her spiritual autobiography to a scribe. The scribe died before it was finished. She took the manuscript to a priest hoping he would help her finish. He couldn’t read the handwriting. Margery prayed and the priest was able to read the handwriting. Margery told him the rest of her life, completing what we know as The Book of Margery Kempe. The manuscript of The Book of Margery Kempe was discovered in the early 1930s and published shortly thereafter, making it a contemporary of Black Elk Speaks. They were published around the same time and have similar layers of mediation between lived experience and written text with various translators and scribes. Both Black Elk and Margery experienced intense visions that often made them ill. I don’t have a point, but the similarities are striking.

I like your framing of Black Elk Speaks (and in a roundabout way Margery Kempe) as modernist. I also liked Joe Jackson's biography of Black Elk, which I read a couple years ago.